Archives

The life of a knife

Several Twitter conversations have taken since yesterday’s post with regard to my question –“What would you take?” They prompted me to dig out another object – a small pen knife. I figure that this could be very useful to have with me on my imagined journey as a refugee.

I was given the little knife several years ago by my husband. It’s a Swiss Army Knife and this ‘ladies’ version came in a choice of colours including lime green, black, red and blue. I went for bright orange as it was favourite colour at the time. I’m sure it was marketed as a woman’s choice of knife so as to offer females a chance to buy in to the Swiss Army brand! Mine has a tiny pair of scissors (for nails and labels only of course!), a nail file (thank goodness-what a life saver), a tooth pick now lost unfortunately, a small knife and some tweezers. I haven’t tried them out on my eyebrows but they are actually really useful for splinter removal!

Every object has a story – and I would hope for those people fleeing their homeland in search of refuge that the familiar objects they take with them may give them comfort in some way.

Whilst not the biggest or strongest of knives my little orange knife would still be very useful and I would keep it close to me. Holding it now in my palm brings my late father squarely to mind. Dad was a farmer and a very resourceful man. His pen knife had a black handle rubbed smooth with use and he kept in his front pocket at all times.

With his knife and a piece of bailer twine Dad would happily attempt to fix most things. Gates falling off hinges could be temporarily secured with twine cut to the correct lengths and fencing tied together too; the cleft hooves of sheep would soon be cleaned with this knife, often easing a pain or discomfort; grain bags sliced open to pour food into troughs for impatient and hungry animals; and at the table (I’m really hoping he washed the blade) apples would be sliced and shared as pudding.

On a couple of occasions I remember Dad losing his knife. Anxiety took hold of him “where could it be?” He would work hard on his memory to recall the last time he had used it. Then off he would go retracing his steps. Once I recall him finding it among the hay bales during harvest (pretty much like finding a needle in a haystack!) he was determined to find it. On another occasion he failed to uncover the knife and explained to us that he would have to buy a new one. It seemed very hard for him to give up on finding the lost pocket knife – he had a kind of unhappy acceptance that he had to ‘move on’!

He returned from town with the new knife – looking very similar to the old one. But he wasn’t sure of it at first – it didn’t feel quite right. But after a couple of weeks work the knife was accepted and took on its role as Dad’s handy, reliable pocket knife.

I often think that if objects could share the stories of their ‘lives’ we would learn so much about their owners. My knife has been very loyal – sitting in my bag all these years, but unlike Dad’s knives not put to much use. For now at lease it will become the subject of some drawing.

Back to my question as to what any one of us would take if fleeing our home. The experience of my father’s relationship with his knife reinforces to me the need we have for objects well beyond their functional purpose. They define us and our cultural beliefs and traditions in such profound ways. The loosing of possessions, leaving them behind, must be in some ways an insignificant part of fleeing one’s homeland. And yet to me it seems such a sharp indicator of how much is lost emotionally and physically, on an individual and collective basis.

A couple of months ago I watched a documentary about twin brothers, both doctors, in their thirties, who followed the journeys of refugees from Syria to France. In Greece they spoke to a girl of about ten staying in a camp with her family. She told them about life back home and how she wanted to be a doctor too. “What did you bring with you from Syria?” they asked her. She reached in her pocket and pulled out two coins – “I brought these”. The brothers were dumbfounded “is this all you have to remind you of home?” The coins were all she had. It seems so distressing but I sensed in her the spirit of optimism – at least she had them – and she lived in the hope that she and her family would make a new start in Germany. In a sense they had nothing left to lose. The massive migration of peoples from Syria and beyond is a highly complex situation which surely requires the empathy and compassion of those in receiving countries to understand and deal with. By taking things to a simple level – a handful of possessions for example -perhaps we can begin to understand and commit to supporting our fellow human beings.

What would you take?

Another day at the studio working through ideas of upheaval and displacement, using objects as metaphors.

I’m struck by the impact that being forced to leave one’s home and homeland must have on an individual.

As objects can suggest so much about their owners circumstances I’m playing with the notion of what objects any one of us would take with us if we had to leave our home and country at short notice and with no certainty of the course and duration of our journey to safety.

Would we have time to collect important documents, cash and cards, our phones, laptops and chargers. Would we find suitable clothing for ourselves and loved ones?

Some of the objects that had seemed essential begin to have less importance as we make our way across boarders, negotiating transportation by land and sea. Would laptops be sold or bartered for food and clothing? Would we always hold on to our mobile phones no matter what in the hope that they link us to others outside the immediate situation.

In my drawing work I have imagined a ‘what if’ scenario. What if all I have is the contents of my bag, purse or pockets? Will they help me to survive? Seemingly useless objects might find new use and thus new meaning. I imagine that whatever these possessions might be, as each day takes me further from home, they take on new significance.

Whilst working with a handful of objects I think about our ongoing fascination with artifacts found throughout history, representing the everyday experiences of our ancestors. We view them with fascination, with sadness sometimes. Here I feel, I am dealing with such artifacts in the present, revealing the plight of thousands of people affected at this moment. My little collection of objects rings with despair – would there be any point in trying to prepare yourself – would a bag full of possessions help you in the long run?

In my last post I referred to a mobile app called ICOON which has been designed specially for displaced people, enabling them to communicate with people of other tongues using universally understood icons. The app is simple to use and really enlightening as to the kind of situations a refugee might find themselves in (it includes an icon for bribery if you can imagine what that might look like!)

One of the icons is a USB cable which I have used in my drawings as it struck me that this everyday object would be incredibly valuable. The USB represents an opportunity to gain a little bit of personal power in a hugely impossible situation.

The Force of The Enigmatic

For a couple of years my work centered on a letter from my father. (The letter had remained hidden among a pile of correspondence for many years after his death). It became the subject of my dissertation and of studio work. My fascination with this object so seemingly mundane and yet packed with personal significance shaped the way I looked at things and drove me to question the validity of our reliance on memory as an accurate source of information.

I questioned the value of memory in assisting our decision making. There seemed to be a contradiction between the (in)accuracy of memory and our unquestioning sense of reliance on it to inform almost all of the choices we make.The letter held all these ideas – uncertainties, questions, contradictions – it pulsed with them and pulled at me inexplicably.

Then within the space of an hour my sense of inquiry and puzzlement was reconciled. Last summer I attended a lecture at How The Light Gets In Festival at Hay on Wye that focused on truth and lies. What constitutes a truth, reality or fact? And how can something be a lie, fiction or unreal?

The crux of the questioning seemed to rely on evidence – if a proposition or reality can be proved to be real or not. Thinking about reality and fiction in this way made me realise just how insistent we are for the reassurance of a reality of any kind to make sense of our existence. Asking questions to prove or disprove realities therefore takes up our much of our time – will the bus arrive on time? Will the medical treatment work? Does God exist? We seek answers for even the most inexplicable scenarios.

Back at the lecture (in the beauty and comfort of a large yurt!) the questions that I have been grappling with about the inexplicable nature of things became plainly obvious. If something can be neither proved nor disproved then it is enigmatic. The pull I had been feeling towards my father’s letter (which seemed to link me to him) was a sense of enigma – the inexplicable, unclear and un-provable. I was seeking answers to something that has no answer and that explains this physical sense of unease – I’m looking for something that doesn’t exist. My father doesn’t exist physically but within the emotional lives of myself and his loved ones he does. The letter is insignificant and worthless in one sense and yet of great value in another.

Things don’t always make sense, are not always real and are often inexplicable – that’s the truth of it, a reality in itself. Figuring all this out has helped and I enjoy working with these ideas and within the physical and psychological space occupied by the notion of the enigmatic.

An enigma by definition must leave us feeling a little uneasy and uncertain. My current work focuses on objects associated with the loss of security with regard to human displacement. I’m trying to identify a handful of objects that best suggest a sense of home and comfort that we might fit into a pocket or bag. I have a few ideas. They appear in my imagination almost like the universal semiotics we use to sidestep language barriers – symbols for male and female etc.

Here is where a sense of the enigmatic creeps in again – I know when I find the objects capable of expressing my ideas they will be perfect in communicating notions of the personal, of home and loss; full of meanings on many levels; complex in that sense yet simply identified.

Last week I was in Berlin for a few days with my husband and we discovered an app which claims to break down language barriers allowing refugees to communicate across languages and cultures using commonly understood icons called ICOON for Refugees. I might find my objects there…

Work Makes Itself

Thank you for your amazing feedback in response to my last blog post. The sincere and heartfelt expressions of support are gratefully appreciated. I had a break and a think and have made a new piece of work about the refugee crisis.

I’m working with objects – or rather the idea of objects, creating new (art) objects fuelled by their power to communicate human experience.

As I work with layers of paper, bringing a series of flat pattern pieces into 3 dimensional form, the tactile properties of garments come alive. As this little coat takes shape I feel waves of experience flow through it. Those moments held in memory – the day the coat arrived – a cousin’s hand-me-down and I pulled it tight round me to fit; the coats’ smell and feel; the way light fell on the fabric on a cold bright day at the coast.

All these notions and more flash through my mind as I assemble the coat – but they are not MY memories but imagined reminiscences. I’m creating a narrative of imagined lives.

Using the child’s coat as a vessel for experience I am working with ideas of disruption and displacement, resilience and refuge.

The work is on show from Thursday 7th April as part of ‘Framework Now’ at The Apple Store Gallery, Hereford.

I don’t know if I can do this..

I’m currently making work about the plight of refugees stuck in Northern France, articulating my concern for those ‘living’ in dreadful conditions from a child’s perspective.

I have made a child’s coat in paper form which attempts to express the vulnerability of children caught up in the crisis. I’m developing the idea of the coat, trying to transom this familiar garment into a tent-like object so that the viewer sees coat and tent almost simultaneously.

I figure that I only need a few universally recognisable tent-like features to make this work but trying to realise this idea has been difficult and I came to a standstill in the studio today. I decided to come back home and do some research into tent design.

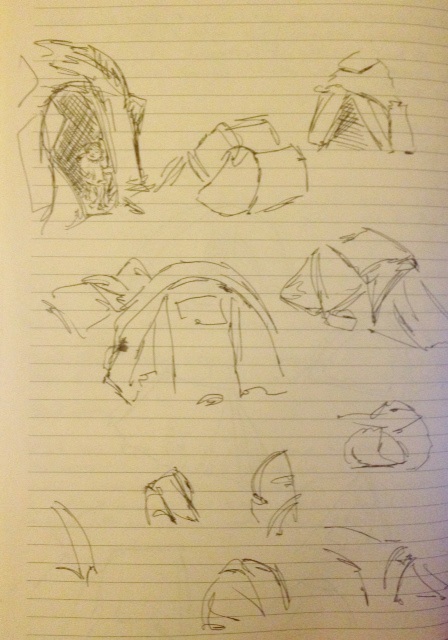

Remember that I have been constructing garments from pattern pieces so I’m thinking in terms of a series of paper shapes to try and create particular 3D form. So I googled ‘tents’ and picked up a few suitable designs which I sketched, and got side-tracked by the most amazing designs and images of glamping.

I wasn’t quite seeing the shape I had in mind so googled images under ‘Dunkirk Refugee Camp’. I realise its awful there as I have been following the situation and have seen media photographs and documentaries but looking at these images, after I’d been working in a objective problem-solving way towards my work, I was hopelessly saddened. God its grim, really grim. I’m not a political person but I feel utterly dismayed by the callous way the inhabitants of the camp are being treated. Their conditions are inhuman and the authorities are by consequence inhumane.

I could hardly continue to scroll down through the images. But I have done, and have sketched the sagging layers of canvas over domed frames. I have been camping for many years and have often sat in the tent on chilly evenings during the summer holidays surrounded by damp clothes and wishing I was at home! Camping is not great even for holiday makers so how it must be for these refugees in freezing and muddy conditions I just dont know – it looks horrendous. And there are children ‘living’ there….

My sketches begin to capture the impossibility of the situation and I’m beginning to see the direction my work needs to take, how I can use the layers of paper to suggest the sagging canvas, the broken tents.

I don’t know however if I have the stomach to do it without wanting to cry and cry – I feel so sick about it all. I think I will need another day, a stronger frame of mind to get on with this one.

I’m following Help Refugees on FaceBook for straight talking informative updates and photographs (mostly on the situation in Calais).