Los Angeles-based artist Suzanne Lacy is renowned for her socially-engaged artworks which she has been producing since the early 1970s. Her work The Crystal Quilt (1985-1987), dealing with the issue of ageing for women, was shown at Tate Modern in 2012-13, and Storying Rape, originally filmed at Los Angeles City Hall in 2012, was exhibited at that year’s Liverpool Biennial.

Lacy’s new project, Shapes of Water Sounds of Hope, was commissioned by Lancashire-based Super Slow Way, and is led by artists’ group In-Situ, which has a residency programme in Pendle.

Centred on the old Smith & Nephews Mill at Brierfield, near Burnley, which closed in 2010, Lacy’s year-long project brings together the local white and Asian communities to talk, eat, and sing.

Culminating in an all-day event and banquet at the mill on 1 October, Shapes of Water Sounds of Hope explores several traditions including Sufi ‘Nasheed’ chanting, Lancashire folk music, and shape-note church singing, popular in America since the 19th century, which can trace its origins back to the North of England.

What did you think when you first saw Brierfield Mill?

As an artist I look at a place like this and think, wow, it’s amazing-looking, and the sound is phenomenal. And it’s also a place where the Asian and white communities worked together very profitably and comfortably, from what I understand – not that there weren’t issues of racism, I’m sure there were. But when people talk to us about the past they’re very excited about the vision of a time when the communities had more cohesion than they do now. So this seems both a beautiful aesthetic site and an extraordinarily symbolic site.

How did you get involved in this project in the first place?

Laurie [Peake, director of Super Slow Way] and I knew each other before, through Liverpool Biennial. And I knew she was coming here, I was friends with her in Los Angeles. She actually taught with me [at Otis College of Art & Design], and when she came here to do this production she invited me to do a site visit with In Situ.

And the focus you’ve got is a musical one?

It’s a prominent image in the work, and I have wanted to work with shape-note music for about 15 years. I worked in Appalachia for a while and I came across shape-note music through Dr Ron Pen and other people in popular culture. And when I started thinking about it, it’s class-reflective, it’s embodied, it’s highly participatory, its structure is democratic, and it’s quite visceral. And I love the a capella sound.

So when I came here, I obviously thought, could we do shape-note in this place? But then, how does that relate to Pakistani and white communities here? And we’ve slowly worked through many of the issues and the conflicts that came up, around Christian and Muslim metaphors, and people from different cultures not wanting to participate in the other because of different sects, different beliefs. So as we work through those, to broaden the circle of participation, what happens is we are encountering in real life the issues that keep the community separate.

What do you mean by “working through”?

Let me give you one example. We had maybe our third dinner or so, and they’d been very successful, and they really do bring 50% white people, 50% Asian people, young, old and so on. Ron [Pen] said, I’m gonna show this old-time video of people in a river baptising someone and I said, “Ron, please, I don’t think we should show that.” But I didn’t say, “No, we can’t show that.” So he left it in, and so I’m sitting there in the middle of the dinner, and on came this video. And I’m thinking, oh dear, and holding my breath. And then the Sufi guys got up and they began chanting and they said, here’s the first chant: “ALLAH…” and a white Christian woman in the back room said, “Why are we singing Allah? I didn’t come here to sing Allah.” And I’m like, “Oh-ho! Now we’ve really got an issue.” And he, the leader of the mosque, handled it extraordinarily well, he was very casual, he was very used to this kind of inter-cultural conversation.

But was there a time when you were thinking, “maybe we can get people across the different cultures to sing together”?

I didn’t and don’t want to push that, like “you have to work with these guys”. But the two leaders, Rauf [Bashir, of the local Community Cohesion Action Network] and Ron, have themselves been having conversations and thinking “wouldn’t it be fun if…” And so the first part of this event-performance will be shape-note, and then there’ll be Sufi chanting and everyone can participate in that. And then the third part of the evening is, through Ron and Ruaf, to try to work out something that works together. And that is totally up to them, and that’s how this kind of work operates. It’s highly participatory.

What can participants expect from the final stage of the project, as it comes together over three days at the end of September?

Basically what’s happening is three things. One is we’re engaging in clarifying people’s ideas. It’s my role as the artist/director to just pull all of that together. And I’m not an equal opportunities artist; it is highly collaborative but collaborative in a very sophisticated way. And the second thing that’s going on is we’re really deeply involved with culture and political conversation, oriented towards empowering people. Now, I wouldn’t be hubristic about that. I don’t believe that artists change the world at all. I think that artists are part of a social change movement. And they offer charismatic and participatory help. And my projects are really good for building capacity, in a person or in a group of people. So we want them both to understand their relationship, past, present and future to this space, [and] that they have some role in redevelopment and regeneration.

And then the third thing is trying to build a production team. And that means training people. Artists in particular are really good at negotiation, reflection, thinking about things. And I’ve noticed, always, when my production people come on board there’s a conflict, because there’s a different rhythm that starts happening. A stage person or a film person has a line of authority and they follow it, and an artist and a community organiser questions everything. I’ve had it happen again and again and again. These two cultures meet, and it’s quite a complex negotiation.

And you’re the artist.

Well, I am the artist but I’m also quite a good and developed producer. So my head operates in both realms. So where we’re at right now within the social practice field is that there are some practitioners like me who come almost – I wouldn’t say from the outside because starting with Allan Kaprow and going to school at CalArts is not the outside – but we really come from an era where we built our own projects from the get-go. We’re used to doing it. We didn’t wait for an invitation from a museum – in fact a museum was the last thing on our mind. So, I tend to know about PR, and stage and management production, but the other half of me is the artist.

But from your position as the artist that you are, is it hard to step back from that political, negotiated, social practice, and think, Oh, I’ve got to concentrate on the art now?

No, I love it. I love the shift. It’s all art.

Shape of Water Sounds of Hope culminates on 1 October 2016 with music and a mass dinner for 500 people in the mill. It will be filmed for a multi-screen installation to be exhibited in spring 2017.

More details including registration to take part in the event can be at superslowway.org.uk

Images:

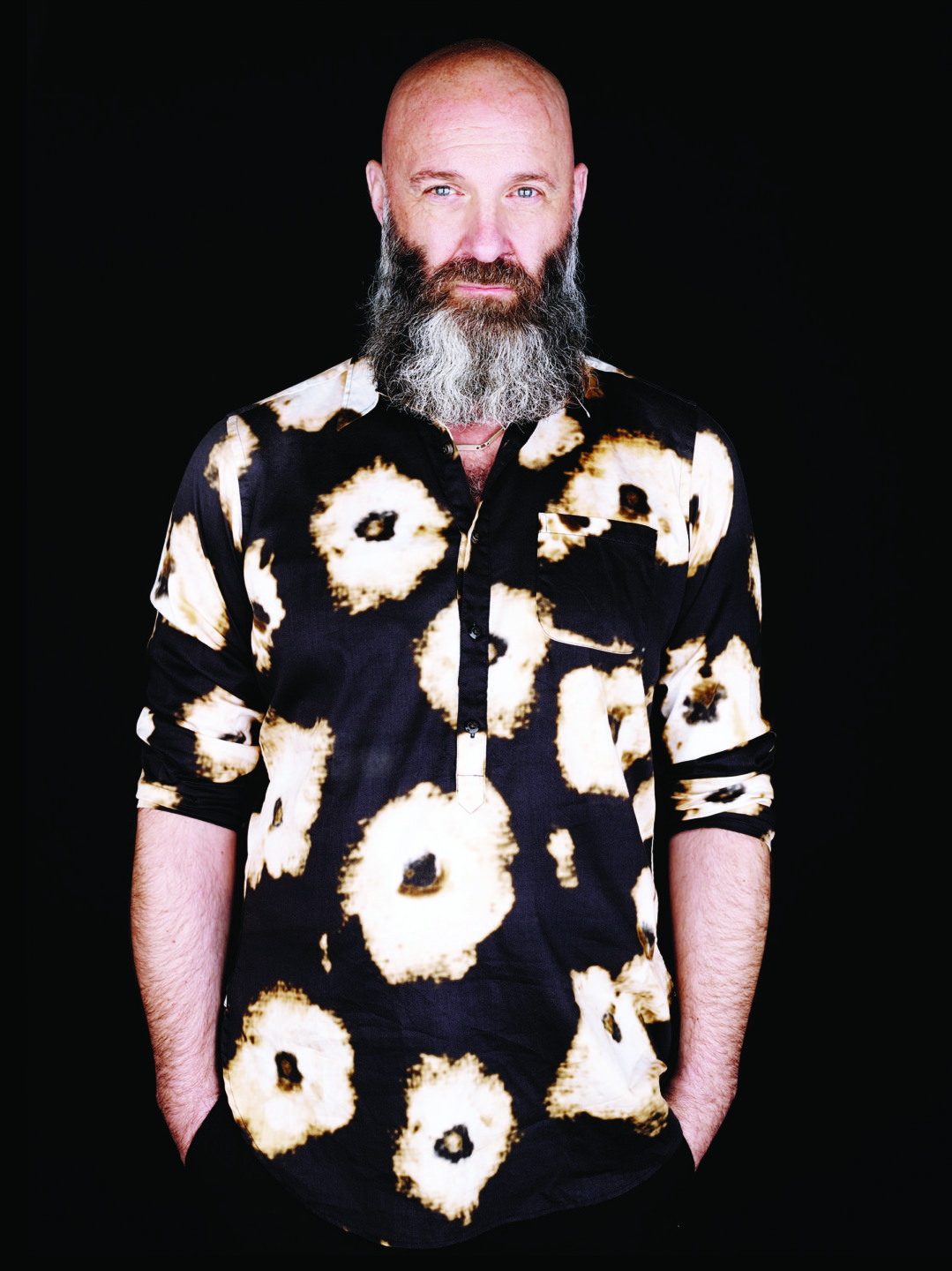

1. Suzanne Lacy (right) in Brierfield Library. Photo: William Titley. Courtesy: Super Slow Way

2 & 4. Brierfield Mill. Photo: courtesy Super Slow Way

3. Suzanne Lacy, Shape of Water, Sounds of Hope event. Photo: William Titley. Courtesy: Super Slow Way

More on a-n.co.uk:

Artangel at Reading Prison: “Powerfully engaging and profoundly moving”

Bristol Biennial 2016: Local, cooperative and quietly rebellious

A Q&A with… Wolfgang Buttress, Hive artist