Since 2006, Laura Oldfield Ford has been documenting hidden and overlooked zones of London in her zine, Savage Messiah. Informed by her walks around the city, she splices together real and imagined experiences and overlapping narratives via text and image.

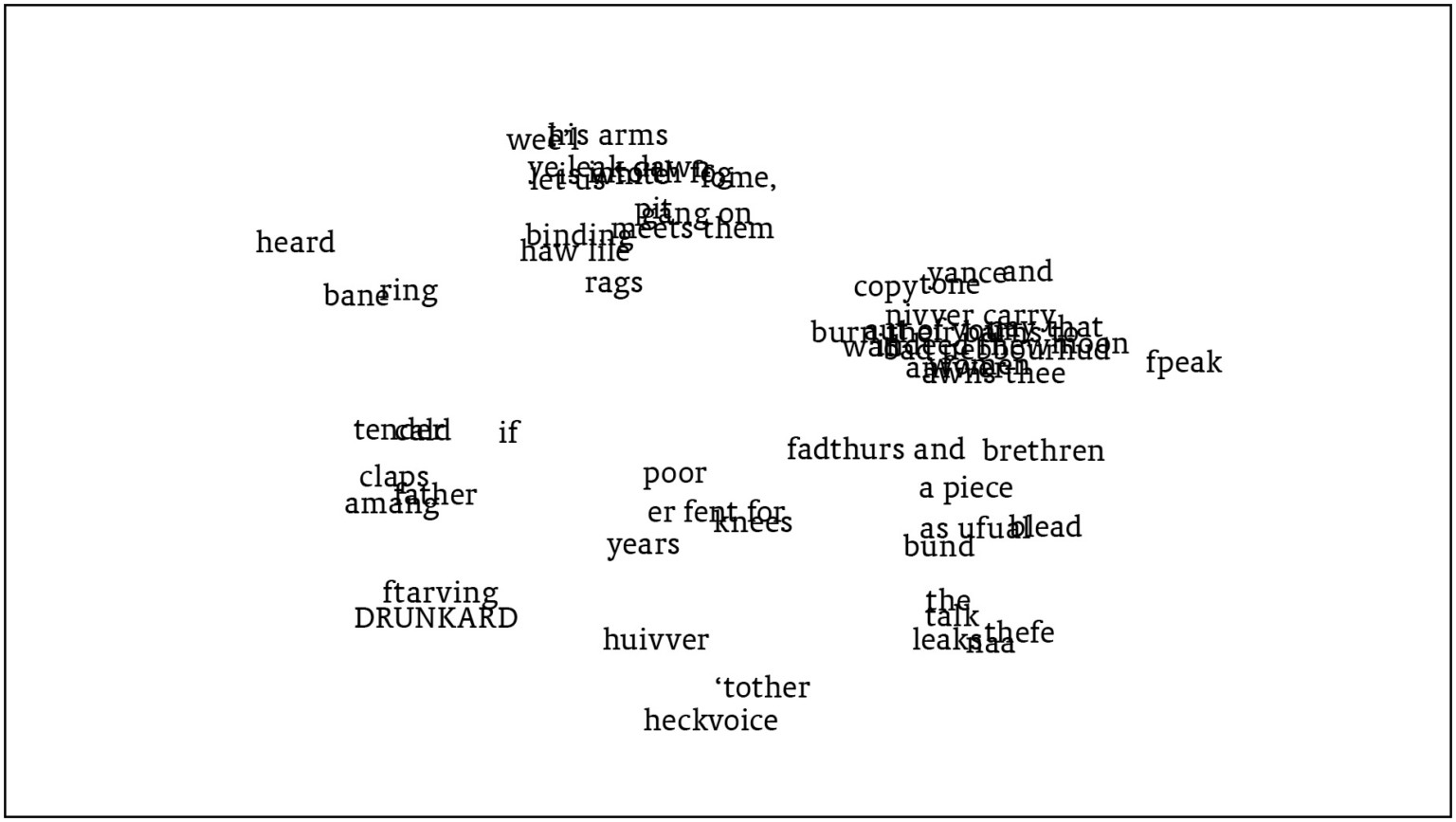

For ‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’, her current exhibition at The Showroom, Oldfield Ford explored the area around the gallery for a year, drawing on her personal and collective memories of this part of north west London and capturing the neighbourhood before the proposed redevelopment of local social housing blocks.

The commission pushes her practice into new territories with large-scale installation and an audio piece made in collaboration with musician Jack Latham. The result is a rich and disorientating visual, textual and sonic journey, in which the artist weaves together multiple voices and alternative pasts, presents and futures.

“Intentionally or not, I’ve always felt like I’ve been recording the scratchings and scrawlings in the margins,” she says. “Even though Church Street [near The Showroom] is just off the Edgeware Road, it feels like a liminal zone, on the cusp of abandonment and rampant property speculation.”

Tell me about your relationship with the area you explore in ‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’.

When I got invited by The Showroom to do the project it was, in a sense, something that I’d always been waiting to do. I already knew that area – Paddington, the Westway, Ladbroke Grove, Maida Vale – a bit through counter cultural scenes from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, and also through militant political action, like Reclaim the Streets taking over the Westway. Then in 2003, I worked with Westminster Council, doing art courses in homeless hostels and day centres, and I became really good friends with some of the residents in the old people’s home. They came from all over the world, but most of them had lived in the area for decades and decades. A lot of them could remember the war, could talk about the Blitz. We spent a lot of time just sitting and talking, allowing those memories to arise. Those relationships gave me a very different perspective on the area.

How did these experiences inform the commission?

I’ve been moving away from psychogeography into what I’ve started to call a ‘sociogeography’. So it’s not just about your own memories and experiences; it’s about tuning into collective moments of intensity, the psychic tremors or the buried currents and narratives that exist in places. I thought about occupation and the squats in Elgin Avenue, the IRA bombings at Paddington Station, and waves of militancy. I was also thinking about these spidery micro narratives, the old people’s stories which include very precise detailed accounts of things. I was able to draw on all of these memories of my own that were fused with these wider collective experiences.

Your writing is dense with sights, sounds and smells. The sound piece is equally visceral. How did you and Jack Latham approach your collaboration?

I think of the audio piece as Savage Messiah, really. Because it’s the same approach, the same method of the cut up and the layering of these different temporalities and multiple narratives. When Jack and I worked on it, we sampled records that had been ubiquitous during the summer of walking around, things that had a certain poignancy, like Frank Ocean’s track Thinkin Bout You which I think really sums up those strange August late summer days, that weird lull you get. During the installation, we really thought about the spatial aspect of the sound; Jack spent a lot of time getting it right with the architecture of that particular space. And time slowing down, and then speeding up; the distortions and the echoes are something we talked about a lot in terms of how you experience the city.

I really like how capitalism becomes surreal in your work. For example, Marks & Spencer’s selling winter clothing on a sweltering summer’s day…

There were all these mannequins with woollen coats and tights and scarves, and it was 30 degrees outside. I love those moments that are like glitches, where capitalism can’t keep up. Heat waves are like that. I think of these moments as points we need to isolate, because that’s when the walls start to melt and the messages that come from capitalism become meaningless and scrambled, and everyone’s collectively together on the streets. These moments are a reminder that they can’t control, they can’t predict.

Getting lost and losing things, places and relationships is prevalent in ‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’. Is the capacity to get lost a necessity in the city?

Getting lost is incredibly emancipatory. Walter Benjamin used to talk about it. It allows you to escape surveillance, to adopt different personas, to have chance encounters. When I write it’s always been this portal that allows me to live in this other realm. It’s not escapist fantasy. It’s a temporary connection with another reality that I know can be realised. When I look back at Savage Messiah as a project, I read it as a chronicle of something that’s disappeared, that’s been lost. That’s not in a melancholy sense of putting something in a museum and having a sanitised version of history and referring to it out of some sort of benign curiosity; it’s much more about returning to something in order to be reinvigorated by a certain moment. You can’t physically time travel, but time isn’t linear, there are time slips and time folds, and you can reinvigorate a certain moment.

London seems like a protagonist in its own right in your work. How do you feel about the way the city is changing?

I’m so emotionally invested in London. It feels like a cliché to say it but it’s like a long-term relationship. I moved here in the early ‘90s, so I’ve been here a long time and the reason I was always so invigorated by it is still here. It’s like this unknowable terrain that no one can lay claim on, this ungovernable place. It’s an incredible city compared to others. It’s always resisted this imposition of order, like Paris succumbed to the boulevards of Haussmann, and American cities which are based on the grid. London’s still got these medieval street patterns that completely defy that order, it’s like a labryrinth. It is a labyrinth.

I like the fact that I can hide out, that I can redefine myself when I’m walking around. Despite all the regulations, despite all the surveillance, there are always these seething currents that could explode at any moment. And they do; there are always sporadic moments of lawlessness and intensity. It can happen at any time, so I never despair.

‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’ continues at The Showroom, London until 18 March 2017; Laura Oldfield Ford in conversation with Nina Power, 21 February 2017; Listening event, 4 March 2017. www.theshowroom.org

Images:

1. Laura Oldfield Ford. Photo: courtesy of the artist

2, 3, 5, 7. Laura Oldfield Ford, ‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’, installation view, The Showroom, 2017. Photo: Daniel Brooke

4, 6. Laura Oldfield Ford, ‘Alpha/Isis/Eden’, installation detail, The Showroom, 2017. Photo: Daniel Brooke

a-n Writer Development Programme

Lydia Ashman was one of five a-n members who participated in the inaugural a-n Writer Development Programme which ran from June 2015 to March 2016. For more information on the writer programme, and to read more of the writers’ work, visit the programme’s blog on a-n.co.uk or use the a-n writer development programme tag

More on a-n.co.uk:

More in the Q&A series, including Lubaina Himid, Mitra Tabrizian, Jenni Lomax, John Akomfrah

Artists’ Books #16: Nathan Walker’s Condensations

Tate Britain’s David Hockney retrospective: buoyantly witty, expansive, and sometimes difficult