A man stares at a mirror and out at us. His face is warped, fragmented, reflecting – we sense his disintegrating sense of self. In his distorted features we can’t help but see something monstrous and frightening, too. We know that, abject and broken, this is how the world must now see him.

Wolfgang Tillmans’ series of photographs depicting a man’s splintered features is called Separate System, Reading Prison. The term ‘separate system’ refers to the penal regime adopted by Reading Gaol when it opened in 1844. Prisoners were kept in complete isolation, leaving their cells only to attend chapel or to exercise, their isolation maintained by having to worship in seats with high sides, cutting them off from fellow inmates even in communal spaces.

When Oscar Wilde was serving his prison term here, from 1895 to 1897, having been convicted of gross indecency, he observed the devastating effects of isolation on vulnerable inmates. He too suffered greatly. During the last year of his incarceration he wrote his extended and agonised letter to Alfred Douglas, his young lover. De Profundis, a title it was given by another former lover – his loyal friend and executor Robert Ross – was finally published five years after the author’s death, but only partially. The complete and uncensored version, all 50,000 words of it, wasn’t published until 1962.

‘Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison’, Artangel’s ambitious, powerfully engaging and profoundly moving exhibition at the now defunct prison (it closed in 2013, having served as a remand centre in its last 20 years) invites us to imagine something of Wilde’s suffering, as well as the harsh conditions of prison life generally, and of what it means to be persecuted for your sexuality. There are over a dozen artists included, their work occupying a few of the tiny cells on each of the prison’s three floors, as well as its chapel and corridors. In the chapel you’ll find the original door to Wilde’s cell, on a plinth of concrete measuring the size of his cell.

Almost as an understated companion to Tillmans’ photographs is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Fear), 1991, a blue mirror in which you encounter nothing other than your own stark reflection. In contrast, his glass bead curtains, covering the entrance to two cells and glistening in blue and white, transform what is minimally functional into something that might be enticing and, for a brief moment, if you half close your eyes, magical. Likewise, Steve McQueen’s gold-plated mosquito netting poignantly transforms a cell bed, catching the pale light as it streams in through a tiny window. Such interventions are all the more powerful for their clearly makeshift and fragile impermanence.

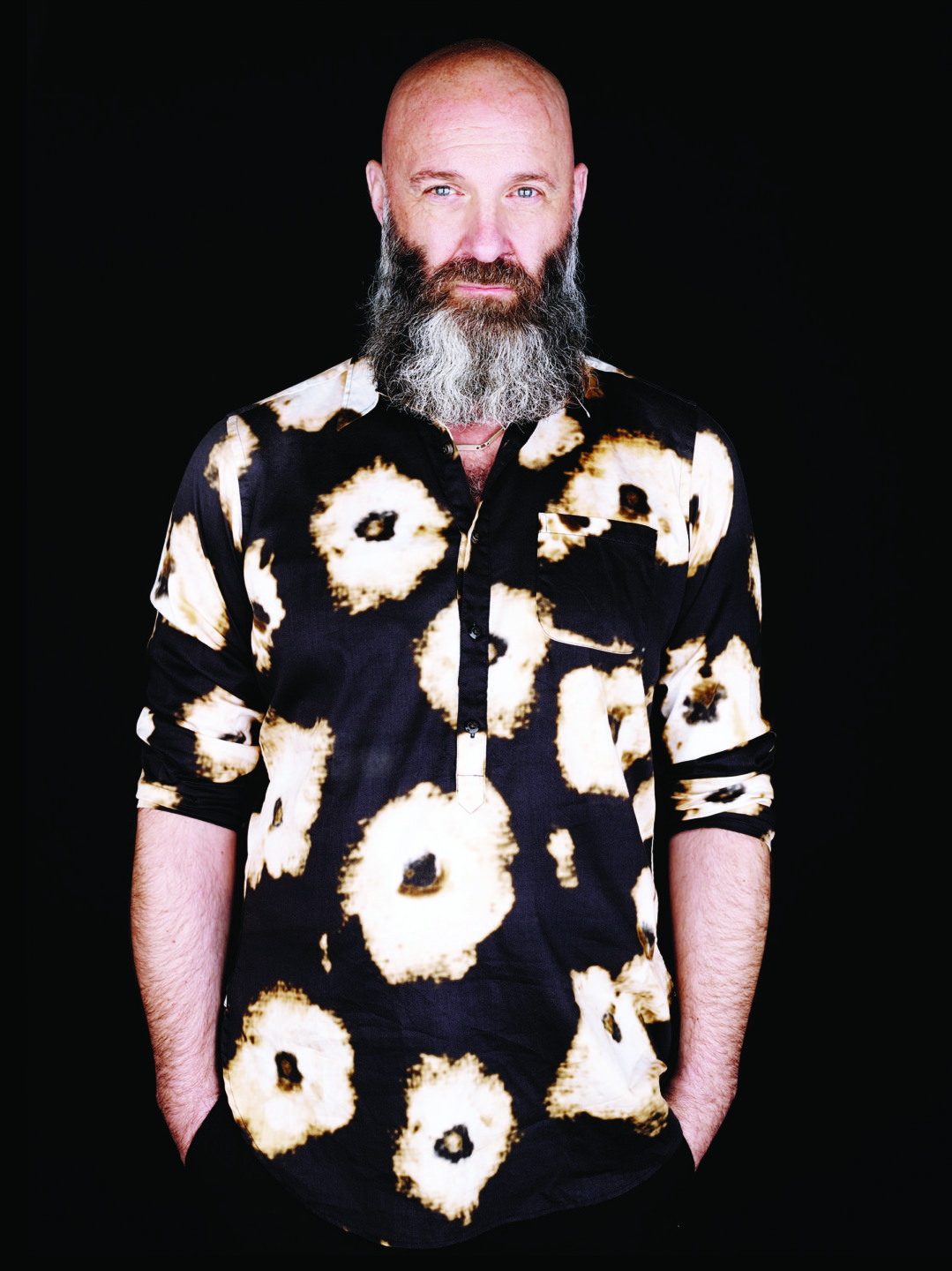

Elsewhere are painted portraits by Marlene Dumas; one of Oscar Wilde, one of Alfred Douglas (Bosie), who wears just a hint of a sly smirk and looks every inch the bounder, and also Jean Genet, who himself experienced incarceration for petty crimes and “lewd acts”. Dumas’s tender portrait of Genet suggests a haunted and alertly anxious young man, his deep-set eyes expressing anguish.

Photographs of Bosie appear in a cell where the walls and bed are otherwise covered in erotic photos of a young man who bears a passing resemblance to him, or at least his contemporary incarnation. The Boy, an installation by Nan Goldin, is a shrine to carnal desire.

Among the most arresting of the artworks are two by Robert Gober, which you can hear before you see. One features a shallow tunnel. Look down and you’ll find a stream bubbling in the chest cavity of a woman– a partially glimpsed mannequin in a cherry-patterned dress and marigold gloves. Another work features the torso of a male figure in a suit, his back to us, Magritte style. A diorama of a babbling brook is carved into his back, the body again acting as a conduit to another world.

A series of recorded letters commissioned specially for the exhibition includes those written by Jeanette Winterson, Ai Weiwei and Gillian Slovo. Slovo writes a letter to her mother, the anti-apartheid activist Ruth First, who was assassinated in 1982; Ai addresses his young son, in Mandarin – you can read a transcript in English – revealing details of incarceration on trumped up charges of tax evasion; while Winterson, in fictional guise, writes to an imagined daughter to whom she’d given birth in prison but was then forced to give up for adoption.

Partly mirroring her own start in life, Winterson’s tale (her characters, Hermione and Perdita, are named in homage to the daughter lost and found in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale) must also be seen as a healing, transforming act. However, the most compelling tale must surely belong to Danny Morrison’s imagined letter from an Irish nationalist awaiting execution for treason.

Live readings from De Profundis will take place every Sunday for the duration of the exhibition. Ralph Fiennes, Ben Whishaw, Colm Tóibin, Patti Smith and Maxine Peak are some of the writers and performers taking part. No doubt it will enrich your understanding of Wilde’s strange and haunting cri de coeur. In addition, tours of the prison, focusing on its Victorian architecture, will take place every Friday and Saturday. But even if you can’t get to any of those, what a richly immersive experience this exhibition is.

Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison is an Artangel commission running until 30 October 2016. Booking is recommended. www.artangel.org.uk

Images:

All photos Marcus J Leith, courtesy Artangel

1. Marlene Dumas, Oscar Wilde (2016), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

2. Wolfgang Tillmans, Separate System, Reading Prison (Mirror) (2016), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

3. Steve McQueen, The Weight (2016), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016

4. Marlene Dumas, Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie), (2016); Marlene Dumas, Oscar Wilde (2016), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016

5. Robert Gober, Treasure Chest (2015-16), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

6. Nan Goldin, The Boy (2016), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

7. Richard Hamilton, Finn MacCool (1983), Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

8. Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, 2016.

More on a-n.co.uk:

A Q&A with… Wolfgang Buttress, Hive artist

Hepworth Wakefield set for one of UK’s largest free public gardens

Hull 2017: After the spectacle, what will the legacy be for artists in the city?