There’s been plenty of talk about the political nature of this year’s Turner Prize shortlist, but of the four nominees for the 2018 prize there’s only Forensic Architecture that can claim to have generated genuine political heat with its work.

Shown during last year’s Documenta 14 in Kassel, this multidisciplinary research group’s video 77sqm_9:26min (2017) was eventually presented to a state parliamentary inquiry in Germany and provoked a rebuttal of its findings by the ruling Christian Democrat party (CDU).

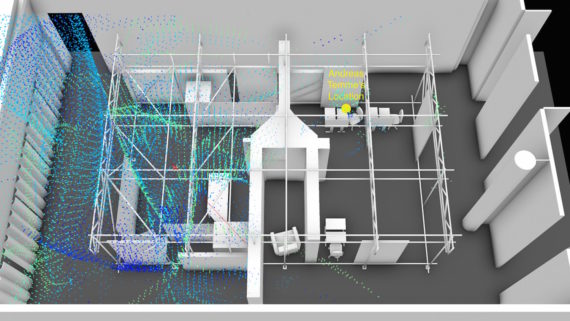

Through digital modelling and analysis using sound, smell and vision, the video unpicks the testimony of a potentially key witness to the 2006 murder in Kassel of Halit Yozgat, the victim of what was revealed to be a coordinated spate of killings by the far right National Socialist Underground (NSU).

Yozgat was shot dead at the small internet cafe owned by his family, and one of the people present in the shop at the time was a German intelligence officer named Andreas Temme. Temme didn’t reveal his presence to the police investigation but his internet records did; in subsequent interrogations he denied witnessing the killing or its aftermath and his testimony was accepted in court.

Forensic Architecture became involved in this controversial case after being approached in November 2016 by an alliance of civil society organisations known as ‘Unraveling the NSU Complex’.

Based at Goldsmiths, University of London, Forensic Architecture was founded in 2010 by architect Eyal Weizman, professor of Spatial and Visual Cultures and director of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths.

The group’s work has included spatial research and evidence gathering for human rights investigations and prosecutions under international law; its 2016 investigation in collaboration with Amnesty International, Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison, won the Peabody Futures of Media interactive documentary award. Most recently, it was awarded the European Culture Foundation’s Princess Margriet Award for Culture.

The Forensic Architecture team currently consists of 15 people from a variety of backgrounds including architecture, design, technology and investigative journalism. Artist and filmmaker Simone Rowat became involved in 2016 when she began working on the Saydnaya project.

You joined Forensic Architecture in 2016 having studied fine art at Slade and then photography at the RCA. How did you become involved?

My background is in fine art but I’d written about Forensic Architecture in my graduate thesis at the RCA; I was looking at image technology and the way it changes the way you perceive the world around you. I first became involved as an editor on the Saydnaya film and I was going to work on just that one project. But it was closely related to research I was doing at the time into modelling and in particular looking at military contexts, disaster relief and trauma and how it could be used in a human rights context in an evidentiary way to extract and understand memory, so I kind of got hooked! There was a growing need for a filmmaker [at Forensic Architecture] and so I came back again for the NSU project. Now I do video analysis and video research as well as working on the presentation of some of our cases.

Can you say more about your involvement with the Saydnaya project?

I came on board once all the footage [of interviews with former prisoners of the Syrian government’s notorious Saydnaya torture prison] had been taken, and there was a producer working on the project as well. I started working as an editor [but] I would say that all Forensic Architecture projects are very collaborative throughout, so although we all have very defined roles technically and in terms of what we’re able to do, you get involved on a deep level quite quickly. I was watching through the footage and understanding what kind of stories could be extracted from the memories and testimonies.

To start at Forensic Architecture on a project like that must have been particularly traumatic. Was that something new to you?

Yes, it was the first time I’d encountered that kind of violence so closely; it was definitely a very challenging project. But I think what really captured me was the ability to work with that kind of content and do something with it that had agency – to not just be commenting on it or analysing the way that images are used but to give a voice to the people that we were working with. It’s very important with every case that we’re very close to the trauma, close to the realities that people have to face, but you’re doing very technical work so you’re going in and out [of that reality, that trauma], and that helps you to cope.

That idea of the work having agency, of it having a very practical and specific end, is striking.

And that’s the first goal, and the guiding force, behind all the decisions you make – how can this investigation have agency, how can it benefit the people that the violation has happened to. We follow the evidence, it’s an evidence-based practice, and in terms of presenting the work and looking strategically at how we are going to show it, that’s always at the forefront.

How does your own background as an artist impact on the way you approach the work?

It definitely influences some things about the way I work. I feel like my art background also helps me learn how to see; spending so much time with images and thinking about images and the power they have and what they’re showing, and how that is adapted in a forensic sense. I’ll bring different aesthetic questions to the group, but I think that everyone is engaging with the artistic side of the work as well – how we show it, how we exhibit, how we present it. That multidisciplinary [approach] seeps in from all of us – it’s hard to draw a line where one begins and the other ends.

Can you talk a little about your role in the NSU film at Documenta and also Forensic Architecture’s recent ICA exhibition?

I worked on the film we made for Documenta but we also produced a new film for the ICA. One of the key pieces of evidence we had for the NSU case was Temme reenacting for the police what he had done on the day of the murder and how he had left the internet café, and almost all of our investigation started from that video. We wanted to make a film [for the ICA] that was hitting that notion of a crime of perjury which is essentially through representation; the video itself is the crime of perjury. So we made a film which shows the physical reenactment process in Berlin and how it used so many tropes of cinema. The ICA provided a space to allow us to come up with other questions, aesthetic questions, but also political questions, which you might not make a film directly for court about.

Why is it important for Forensic Architecture to show in cultural venues such as art galleries?

A really important function of showing in cultural spaces [is exploring] the other questions that can come up from this kind of work. What does showing in an art context bring about when you’re talking about images and the life of images, and how you can read them and analyse them and present them? So that’s a very important function of how we use galleries. But another function is that we use them, like with the Documenta piece, to create politic mobilisation around a work. So sometimes if a case hasn’t gone to court or we need to create political pressure for it to be seen in court or even to initiate a case, you can do that by showing in cultural spaces. So with the NSU case, showing the work just down the road from where Halit Yozgat was murdered, during Documenta where there was so many people who came to see it, put pressure on the German parliament. It was then shown in two public inquiries and it created a lot of conversation in Germany and brought the issue back to the forefront.

You’re working on a project about the Grenfell Tower fire and asking the public to share any footage they might have. What does the project involve?

It really came about from us all coming to the office the next day and just being completely shocked and really touched by what had happened. And there was something really clear there: an architectural connection, a media connection, and there was so much footage. And so we were thinking, is there any way that we can contribute to understanding what’s happened, because this is on our doorstep and how could it have happened in London in these times? We’re adopting some of the methodologies that we use in a remote violation in a war zone or a missile strike or bomb site [and asking], can we begin to understand what happened on the night from the footage that already exists? It’s a call for Londoners to contribute to understanding how this tragedy happened, but also something for Londoners to have as an investigative tool and a social history.

And what will you do with the footage?

We’re projecting the footage onto a model of the building and eventually it will become a complete record of what happened on the night so you can navigate through space and time. At the moment we have 180 videos covering around two days of video time, and most of the footage is from later on in the morning. In our call for footage we’re trying to get a much more comprehensive understanding of the early hours and how it began, the emergency services’ response and how the fire spread up the building. At the moment we’re really just in that phase of collecting footage and beginning to projection map – which is a very time-consuming process.

The way Forensic Architecture works with images and digital information is very pertinent to contemporary culture, particularly the way that we increasingly experience and understand the world through imagery.

I think a lot of the way we understand things that have happened, and the way we experience them, is through the media and through social media, and things linked to survelliance and satellite images. So it [Forensic Architecture’s work] stems from this idea of how can you investigate something when you can’t be there at the site, when you can’t have access to it. So the images and the media are what you have in order to try and understand what happened and so it’s a natural progression that the things that are recording all this, and form a large part of our media landscape and how we engage with the world, become our essential tools to engage with to try and unpick what has happened. We always try and think about that when we’re presenting the work and also to contextualise everything – so we never just show an image, we always show it in the context of how we placed it somewhere and how we connected it to another image or another piece of media, and how it formed a bigger narrative. It’s never just an image – it’s an image and a context.

Images:

1. Forensic Architecture, The Ayotzinapa Case: A Cartography of Violence

2. Forensic Architecture, 77sqm_926min

3. Forensic Architecture, Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison

4. Forensic Architecture, Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison

5. Forensic Architecture, 77sqm_926min

6. Forensic Architecture, Grenfell Tower Fire

More on a-n.co.uk

International Report: Printemps De L’Art Contemporain 2018 festival, Marseille

![Simon Denny, Blockchain Visionaries [with Linda Kantchev], installation view, Berlin Biennale 2016. Courtesy: The artists, Berlin Biennale and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/ Berlin/ New York. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul](https://static.a-n.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SD_BlockchainFutureStates_Space_BerlinBiennale_2016_PhotoHans-GeorgGaul_007_preview-300x200.jpeg)

DACS’ report outlines how blockchain technologies can improve sales and transparency of art market

The new Royal Academy: no imagination or cost spared in David Chipperfield upgrade