But, this is where I catch my breath, on its left hangs This is a room I’ve never lived in, the piece that brought the return of the repressed Hitler salute in my work, dare I write it, a small outfit where a child’s upper body becomes a huge outstretched arm. A black sleeve crocheted from wool that stained my hands, with a pink and white cuff or is it a collar – little crochet pillar in underpants, incongruous and ordinary, pathetic really, but its verticality bold, almost brazen now, and I go still at the curator’s choice of placing these pieces together.

On its other side Charlotte Brown‘s etchings, Necklace I and II, coils of pearls starkly black against white paper, like ink transferred from fingertips. There are undercurrents: of value and violence, beauty and stricture, pearls (presented by husband to wife, their lustre a sign of wealth, status) burning into skin like acid into zinc. The sooty colour renders something precious punishing – those are the pearls that were his eyes – Blaubart’s maybe? And placed next to This is a room I think of the dark stains I imagined on my hands. And then they take on yet another sinister hue – think of all the valuables taken off Jewish men and women on arrival at a concentration camp.

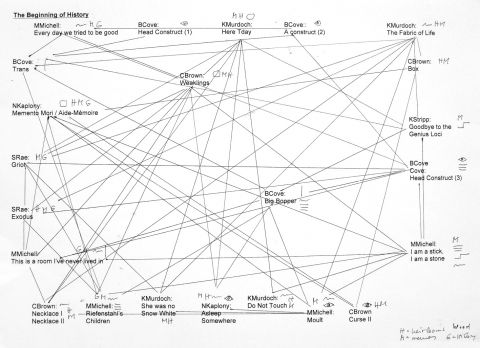

Connections keep shifting. Nick Kaplony, curator laid out the exhibition by shared formal aspects, small details, colours, shapes, thus allowing for surprising juxtapositions. Moving through the show, even mentally as I lie here, is a vertiginous endeavor, where, as I start to ‘see’ the pieces, relationships emerge, and with them new meanting.

On to Nick’s Memento Mori / Aide-Mémoire, two small photographs of some of his parents’ professional tools, shown oversized. A denture’s grimace; eye-shadow with an almost atomic tint, crimsonish purple, now you see me, now you don’t. Together they threaten with the knowledge of transitory beauty, even death and decay, and strive to withhold it, cover it up. How light and hopeful Asleep Somewhere seems now, even if those lashes are tools of the trade too. Although hugely enlarged their delicacy carried on golden light, lure us in, and for an instant we imagine life as a happy song and dance in the rain. The dentures don a trail of history though, of gold teeth broken from mouths, and that black sleeve swings back into view, and a child unaware of what it stretches towards.

I turn to Kate Murdoch‘s Fabric of Life. A series of swatches, treasured heirlooms, fixed in embroidery-loops with edges painted dark grey and hung from threads. They’d move in a breeze: a tiny doll’s dress, part of a patchworked tea-cosy, such pretty fabrics, colours, textures – but then the top of a stocking and its suspender, weirdly creepily flesh-doomed, undercuts these pleasures. A woman’s body, brought down not only by notions but the ways of all flesh. Desire. Inflamer and destroyer of nostalgia.

Mourning and a thread left hanging… Kate‘s nana made this, owned this, mending, stitching, hemming in, making her home beautiful. We can’t know how much is masked: a hard life, fraught roles and relationships, domestic and other, work and worries. Now we may look but not touch. Memories are made of this, a shard here, a rip there, for us to ponder over. The artist has chosen and cut to fit, in one gesture tender, restorative and destructive, swatches hanging lightly, with air around them, weighted with loss.

Karen Stripp‘s installation Goodbye to the Genius Loci, speaks of a different loss: a house left behind, a home. Her installation of small colour photos with white edges, showing fragmentary views of the house’s interior, corners, walls, a bed, a fuse box, are arranged to fill a circle on the wall, with gaps between. On its sides hang four larger framed photos in gradations of dark ochre and black, taken at night, haunted by memories that have already become untethered. Last glimpses of life lived there, its patina.

Assembled on the floor as if fallen from a mirror: photos scattered around a large one of a figure laid out from bits of the house’s timber, pieces from age-worn bannisters, shelf brackets, maybe chair legs. The genius loci a partial figure, expired too. The whole set-up like a gravesite. What remains when something falls apart? There’s a sense that this installation could grow indefinitely, spread, and in the end overlay the original house, replace, alter, in/through memory. The act of remembering changes the thing we are trying to remember.

(more below —>)