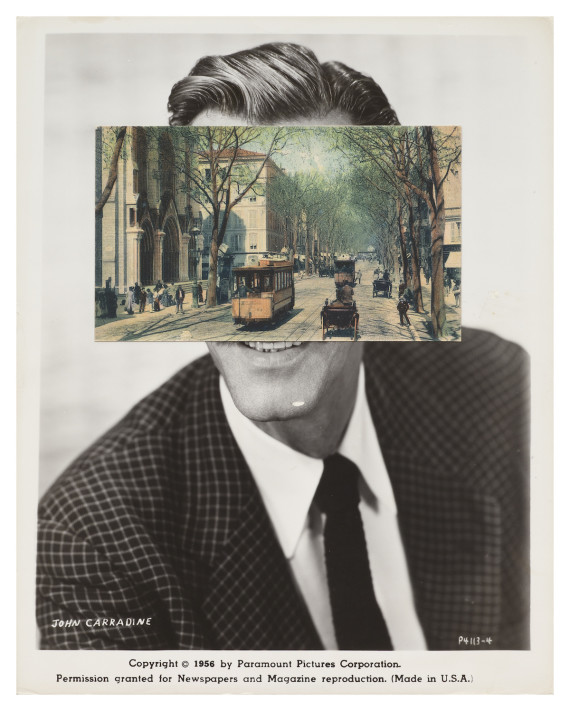

John Stezaker came to prominence in the 1990s with his arresting photographic collages constructed from found images. Now internationally acclaimed, Stezaker’s work has been shown at biennials in Venice, Sydney, Paris and Ljubljana, and is held in public collections including Tate and MoMA.

The Worcester-born artist is now curating his first ever exhibition. Held at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, ‘Turning to See: From Van Dyck to Lucian Freud’ presents photographic collages by Stezaker alongside paintings, prints, photographs, drawings and sculpture from some of the most celebrated names in art history.

The exhibition’s centrepiece is Self-portrait by Sir Anthony van Dyck (c.1640), acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2014 and touring to public galleries across the UK, 2015-18.

Turning to See also features portraiture and self-portraiture by artists including David Bomberg, Helen Chadwick, Gustave Courbet, Lucian Freud, Sarah Lucas and Pablo Picasso, taken from the collections of Birmingham Museums Trust and the National Portrait Gallery.

I understand this is the first exhibition you’ve curated?

Yes, that was Lisa Beauchamp’s idea [curator of modern and contemporary art at Birmingham Museums Trust]. Collage is a way of collecting and bringing things together – it’s curating in a microscopic way. I enjoyed going through exactly that process with the National Portrait Gallery. It was extraordinary being able to say, “Oh, not that Rembrandt”. And then when I came to Birmingham, I couldn’t believe it – there’s a whole conglomerate of collections to access. I felt like a kid in a sweet shop and I went through an initial phase of pure enthusiasm for images.

And the van Dyck is on a national tour?

Yes, the National Portrait Gallery have allowed the curatorial decisions to be taken on by a bunch of hooligans – putting artists in charge! I’ve enjoyed the process but I do feel I’m treading on unknown territory. It’s an odd position to be in – that of a curator. I had a small reproduction of the van Dyke in my studio. From looking at that came an interest in ‘turning’ as a theme. There’s something strange about the work and it’s unlike anything else he painted. I think the two parts of the painting are the two parts of his valedictory statement. He is saying, “this is the dexterity with which I can paint, the legacy of my hand, and this is me” – there’s a tension at play.

How have you selected works for the exhibition and how does this process relate to making your own pieces?

Well, curating is different from making work. I’ve discovered you have to do a lot of compromising when you’re curating and I don’t compromise in my work. It’s a different kind of process. You could say I’m using the eye I use for my work to select things but I’m trying to bring together pieces within a theme. This theme of turning very much relates to my work. My Marriage pieces all came out of looking at Pablo Picasso’s work of the 1940s. During the war he made portraits that involved three facets – face on, three-quarter view and profile – and Angus McBean likewise. I can’t work with three facets, only two. Two facets transform the face into something mask-like. I wanted to look at turning historically and within mythology, and to look at turning in different movements and directions, hence the inclusion of my good friend Helen Chadwick’s Vanity (1986). It’s kind of an awkward piece but very beautiful.

Are other works you’ve selected all long-term fascinations or newer discoveries?

There’s a mixture. I was completely guided by the image. If you think of the collection at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery you think of the Pre-Raphaelite collection and Edward Burne-Jones had to come into it. I wanted to show Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (1894) by my favourite of all artists, Walter Sickert. Sickert does something amazing with this drawing. You can feel the self-consciousness and pain of the model in his partial exposure and awareness of us.

How did you plan the display?

The van Dyck is the star attraction so I decided on a rather grand arrangement on the main wall. There’s a historical and political connection between that and Henry Marten (Martin) by Sir Peter Lely (1650s). The bodily presence of the brush next to the body in the van Dyke accounts for the proximity of the two [1937] self-portraits by David Bomberg, framed on either side by the sinuous, Pre-Raphaelite turning. Works by Chadwick, Gillian Wearing and Lucian Freud are the centre points of the other walls. I also wanted to include Sarah Lucas. There’s an ambiguity in a number of the works of women.

The strong, ambiguous women contrast with the more passive female models of the Pre-Raphaelites.

The gaze is all about gender.

And the inclusion of the Henri Gaudier-Brzeska bronze?

Maybe it’s a bit of a joke in the heart of it all. Having him (Alfred Wolmark (1913)) looking at the van Dyke and him looking back. I didn’t want a big empty space in the exhibition – I wanted something in the middle to set off new conversations.

You’ve described the images in your own works as ‘virgin’ images – unknown faces that give you licence to slice and rearrange. In the exhibition you’re dealing with some of the biggest names in art history and their famous models. How have you handled this difference?

I hadn’t thought of that. I’ve been thinking that the only thing I don’t like about the show is the presence of my pieces. It’s a terrible admission. I feel they’re a little out of place. I think you’ve put a finger on what it is. Every single other one is important in some way but I am creating personae. They’re the odd ones out. I think that there’s something more real in my works than the images they were composed from, however – they seem more vulnerable, maybe because of their sexual identity and because they look in different directions. It’s similar to turning. Curating the show revealed something to me about my own work that I’d done without realising – a doubling of the gaze.

Some of your works in the exhibition are new pieces. Are they made in response to the collection of Birmingham Museums Trust?

I’ve made some works in response but they’re not on show. It seems odd to be back in the place where I first encountered art. When I was very young I came to the museum with my great uncle who was a stained glass artist. He introduced me to Burne-Jones here in this building. I remember his Pygmalion series (Pygmalion and the Image, (1878)) particularly. There’s something creepy about the moment the sculpture becomes alive – a tiny bit of pink in the stone figure that struck my childhood imagination. Burne-Jones has been an abiding fascination for me. I’ve made a new eight-part series called Painting which relates to this. I think there is a plan to show it in the future with the Pygmalion series.

Have you further plans to curate?

I’m doing an exhibition at York Art Gallery relating to a family bequest of Paul Nash’s work and British surrealism, with a show of my works nearby. I’ve also another in the pipeline.

Turning to See is on display at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery until 4 September 2016. www.birminghammuseums.org.uk

John Stezaker will discuss his work and the process of curating the exhibition at a talk at 7pm on 9 June at Aston Hall, part of Birmingham Museums Trust

For more Q&As with artists, including Alex Katz, Lawrence Lek, George Shaw and Marianna Simnett, use the Q&A tag

Images:

1. John Stezaker, Mask (Film Portrait Collage) CLXXXV, 2015. © the artist, courtesy The Approach, London

2. ‘Turning to See: From Van Dyck to Lucian Freud’ at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery (28 May – 4 September 2016). © Birmingham Museums Trust

3. Sir Anthony van Dyck, Self-portrait, c.1640. © National Portrait Gallery, London

4. John Stezaker, Mask (Film Portrait Collage) CLXXXVII, 2016. © the artist, courtesy of The Approach, London

5. John Stezaker, Marriage (Film Portrait Collage) CXI, 2013. © the artist, courtesy The Approach, London

6. Lucian Freud_Self-Portrait_1963_© The Lucian Freud Archive_Bridgeman Images_National Portrait Gallery

a-n Writer Development Programme

Anneka French was one of five a-n members who participated in the inaugural a-n Writer Development Programme from June 2015 to March 2016. She is a writer and curator based in Birmingham.

For more information on the writer programme, and to read more of the writers’ work, visit the programme’s blog on a-n.co.uk and use the a-n writer development programme tag.

More on a-n.co.uk:

Birmingham Big Art Project: five artists’ proposals for £2m permanent public artwork

Rogue Studios: can artists still afford to live and work in Manchester city centre?